Plans are useless, planning is everything

Planning may fill you with a sense of dread – not again! The annual planning season is usually a time of endless spreadsheets and meetings and brainstorms and…so why should we plan at all? The answer was pithly summed up by – anecdotally – Dwight Eisenhower, who at one point is reputed to have said that “plans are useless, planning is everything”.

This is sometimes interpreted – lazily – as saying that the result of planning work is useless, and that only the process itself matters. While a possible way to understand Eisenhower, this is too facile. What we believe this means is rather that planning is something that you should engage throughout the year. Planning – in this sense – is the goal-reflection cycle that fuels your team’s success.

Planning is never over – you need to revise plans and goals as the game changes, and this means that you should have a planning mindset – and not rely on dead plans that have been produced at some time in the past. We read Eisenhower to say that we all need to be continuously engaged in planning and revising our assessment of the world around us.

Plans are what happens when planning ceases, and when you stop using that particular frame of mind in your daily work – they are ossified thoughts and ideas about what to do, and should not be elevated to commandments.

Always be planning, never settle on a plan. To some this may sound both hard and horrible – why not just set a goal and leave it at that? Well – because we play an infinite game with no clear conditions of winning.

The idea of the infinite game – as explored by James P Carse – is an idea that highlights that business is a different kind of game, than, say, chess. Chess is a finite game with clear conditions to determine a winner. It has a beginning and an end, and the purpose of playing a finite game is winning it. The purpose of playing an infinite game is playing it and evolving the game. You don’t win in business – contrary to what millions of business self-help books argue, and you very much do not win in politics.

In infinite games planning is everything, and plans – finite goals for winning – are useless.

Different kinds of planning – strategies, plans and campaigns

In this chapter we will discuss three different ways of organizing your work as a government affairs professional. They are partly complementary, and different styles will fit different people. These models are there to help you think about the future, but they are not by any means silver bullets.

The importance of organizing your work and thinking about the future may seem obvious, but the real value is not in building an ability to predict the future and control it – but to understand the space of the possible. What can happen, and what would I do if it did indeed happen?

Again, remember Eisenhower: plans areuseless. But planning is everything. Planning, looking at the world around you, thinking about it together with your team – that is absolutely central.

It builds what Stanley McChrystal calls a ”shared consciousness” – a shared model of reality, and allows you to not just delegate more effectively – it also creates a joint sense of what it means to make progress, and to improve. A plan is key to help the team keep score of how things are going — and sets out the general rules of the game and how they can be changed.

The importance of this was impressed on one of us (Nicklas) when he gathered his leadership team for an offsite, handed them cardboard, crayons and paper and then divided them up in to three groups with the mission to make a board game that represented what we do as a government affairs team.

The challenge here was to take an infinite game and translate it into finite form – and really think about what finite games hide in the larger infinite game of politics and business. The decomposition of the world into component part finite games is a helpful mental model.

The three groups went off and spent significant time working on their board games. The only requirements they had to meet was that they would show how you made a move in the game, and how you kept score and under what conditions you would have won the game.

When they were done, we toured the tables and played a few rounds of each game. The result was interesting and illuminating. Not only did we have three very different board games – winning was also different in all three.

One game was a chutes and ladders type game following a piece of legislation through the legislative process, aiming at stopping a bill. The idea being that what we do ultimately is shaping and working with the legislative process.

Another game was positional, and if we had control over a number of ”commanding heights” we won, being able to shape public discourse and debate effectively.

The third game was connective and was about building networks that would protect against attacks – in this game we won if we had built an effective network to protect the business against attacks from competitors.

All three models are good models of what a government affairs team is likely to do, and all valuable — but they are very different. Someone optimizing the network is likely to prioritize differently than someone stopping a bill or seeking to hold a commanding height. Spelling out what the game is and how it is won harmonizes those actions. Realizing, also, that there are many different ways to decompose the complexity of government affairs into more finite models is an important insight.

This is a strong reason to plan together, and to spend significant time doing it. It also allows you to understand what the problem really is. The most common challenge in many of the plans and strategies that we have worked on is that the team is eager to come to solutions, and not enough time is spent on understanding what the problem really is. What is it that we want to accomplish and why?

Take a simple example: on a recent case one of us led a planning session in which it was assumed that we wanted to stop a piece of legislation entirely. This was not challenged by anyone, until the team had a conversation with our engineering lead for the product most affected who blurted out ”this is much worse for our competitors than us!”.

Suddenly the basic premise of the plan – that this was bad for us – was swept away! What we should have done was to plan how to shape the legislation into an advantage – not stop it. Back to the drawing board and to the planning, and when we reconvened we all agreed that if we had just spent a little more time on defining the problem, the question we were being asked, we would have saved valuable time.

And then, in addition, we should have asked the much harder question of how this affected the ecosystem as a whole – because reducing it to a zero-sum game between us and our competitors is ultimately also shortsighted. Really good plans expand the playing field – they do not just level it.

The three models below all deal with these problems in different ways, and they all offer interesting ways of working. You will probably prefer one, but we encourage you to switch around between them – since they provide different mental frames for understanding the work we do.

Strategy and story

Strategy is a terribly abused word. As detailed in great length in Lawrence Freedman’s magisterial and eponymous book, strategy can be forced into meaning almost anything from plan to general disposition to ideas about what to do generally. Freedman ends his 800+ page book by saying that most strategy seems to have been useless, but one specific format – the narrative strategy.

In a narrative strategy you describe the world from a future point, highlighting how you got there through core milestones and what happened in the meantime. The narrative strategy thus resembles what is sometimes called premortem – a story of how you failed or succeeded at something from a future point in time.

The narrative format is great because it has this innate capability to call bullshit on you. If you write a story that is unrealistic or contains wishful thinking, the story will show it. The logic of the story will make it obvious that you are fibbing and that what you are describing could not realistically happen. The story demands a certain mimesis – a certain realism – and so checks our more optimistic tendencies to believe that we can accomplish anything.

Working with narrative strategies is surprisingly simple and interesting. The core steps are simple these:

1. Ensure everyone in the planning team writes two 1-2 page stories about how you succeeded with your objective and how you failed from a future point in time. Ensure that you do not collaborate.

2. Share stories and code them for similarities and differences.

3. Meet and discuss what the master story should look like and what it implies in terms of actions, investments, resources and priorities.

4. Consolidate the story with the actions and use as a plan.

This may feel a bit light-weight to many, but the process of doing this is surprisingly effective. It also helps to understand what stories different people bring to the table, and how they are seeing the problem. The discovery value of the narrative strategy approach is great — but it leaves the issue of the objective a little bit too open. Before the writing assignment can be shared a common objective needs to be defined and clearly examined.

Missing this step can be fatal since you will end up with a rigorous plan to go somewhere you may not want to end up.

To prevent this, there is another important piece of work that needs to be undertaken. Strategy guru and thinker Richard Rumelt has called this phase the diagnosis, and has pointed out that it can be reduced to the deceptively simple question ”what’s going on here?”

This question – what is going in here? – is key. Spending ample time on sorting through what is going on is time well invested, and you should make sure to build on data and numbers, but not anchor only on them. The answer to the question of what is going on here is a story – the story you are caught in, the story we spoke about in the first chapter. In diagnosing the situation you detail this story and the context you are stuck in. This will help you understand what the objectives are and how to plan better.

Diagnosis involves seeking out critics, commentators, employees, leadership — you need a broad set of inputs and then sit down and synthesize them.

In Rumelt’s model a diagnosis is then followed by devising a global policy – a direction for the strategy – and then developing consistent actions under that policy. A policy needs to be concrete enough (not ”improve the world”) and seek to build a strategic advantage – a position of greater strength than you are now in – and this in turn needs to be understood from the diagnosis. What are your strengths and weaknesses?

Now, with the diagnosis and the policy in place you can map out actions and check them for consistency with each-other, the policy and the diagnosis. Nothing you do should detract from the policy and from building your position of strength. Actions are concrete – they happened or they didn’t. This is the nitty gritty of the work – these are the things you will ask people to do as a consequence of the strategy, and over time you will have to evaluate if they work (we will get back to this later in this chapter).

A note here on strength. A lot of government affairs quickly reverts in to defensive stances. Companies under fire just want the problems to go away. Even so, a government affairs team must have a focus not just on defending the company, but also building a stronger position for the company long term. Otherwise the company will be locked in a defensive pattern, and this is catastrophic over the long term.

So, let’s recap. In the strategy model you start with a diagnosis, then you devise a global policy and flesh out actions from there.

1. Diagnosis. Find out what is going on here. This step uses a lot of different inputs, synthesizes them and brings a robust diagnostic story about the company to the strategy process.

2. Global policy. Build a general sense of what the objective is, what you are doing. This needs to be concrete and have focus – you need to identify a centre of gravity in the company’s environment and concentrate force on that.

3. Consistent action. This is where you look into the how. Premortems or narrative strategies are great tools for discovering the how here, helping the team imagining reaching the goal or objective defined in the global policy.

Now, back to our narrative strategy formulation. You have the diagnosis of the world and you know where you want to go. Now write yourself back in time from a future point of success as well as failure. By doing so you will be able to start uncovering elements of the global policy and the consistent actions you need to take.

You combine the story and the strategy – alternating between them and exploring different options in order to then iterate on the story.

As you iterate on this process – objective, diagnosis and then narrative to uncover a global policy and actions to consistently implement it – you will also build something else that is really important and valuable: a silent decision support guide.

The reason stories are so effective in crafting plans and strategies is that they do not only allow you to explore the possible paths through writing, they also build a shared understanding through that story of what we need to do.

A company that has a story of how its future should and should not go, is a company where everyone understands why decisions are made and can make more decisions themselves, autonomously, without feeling that they have to escalate everything. The story becomes a decision guide, allowing everyone in the company to think strategically through the shared story.

This may seem like a small thing, but especially in a fast growing company it is absolutely key. That story, that narrative, holds everything together and not just guides decisions but delegates them more or less automatically as long as it seems clear what decision will lead into the successful story of the company’s future.

Sure, you can get things wrong and disagree – but compare that with the company that has no shared narrative about the future. There, empoloyees will defer to the CEO or founders and escalate everything, because the general feeling will be that they are the only ones who know what is going on and what to do.

That slows everyone down and ultimately leads to an inability to engage in efficient organizational decision making.

The combination of narratives and planning, of story and strategy, then also ends up building a culture.

Devising a plan – the OST-model

Different teams prefer different ways to think about plans. We have both used several different methods for planning, and find it helpful to alternate between them. Even if the narrative model has definite strengths, other models also have a lot of value. We want to show you a few of the other models that we have used, just to both give you a choice and to also remind us that there is no single one method that is best for everyone. The first model we want to talk about is the OST or (C)OST model. The acronym stands for context, objective, strategy and tactics. In this model the word “strategy” is used in a somewhat different sense than in the previous section and we will explain why.

The OST-model is usually used to develop a specific plan for a specific objective in a policy area. It concentrates the thinking to an area, and lacks the overall direction that the previous approach had. Yet, it can be helpful in drilling down on what we want to do. We will take an example here – a company wanting to deal with the copyright policy debates.

We start with the objective. What should the objective be in dealing with the copyright policy debates? It is worthwhile spending some time on thinking this through, and there are several alternatives: stop any reform, ensure that copyright costs don’t explode — but it is usually better to try to find a way to frame the objective that is quite broad. We will use the following:

Objective: To ensure that copyright legislation and practice does not significantly impact our ability to innovate or our cost structure / business model profitability.

This objective is very general, in the sense that it does not point to any specific bill, but concrete enough that you can track it. The one criticism I think would be legitimate here – and it is worth thinking through – is if ”ability to innovate” is clearly understood. What this means seems less obvious – but you will often find this objective in the tech space, and so we will allow it.

Next comes the development of the strategy. In the OST-model, the strategy is the general solution to the problem posed by the objective. The strategy provides an approach that then will govern the choice of tactics. Our strategy will be this:

Strategy: Make the copyright issue an economic issue best handled in the market between equals (to avoid legislation that tips the tables in favor of incumbent copyright holders).

This strategy implies something about the other side’s strategy. As you will have seen, the OST-model seems to lack a clear diagnosis – and this is usually best handled by starting with context (C).

Context is a version of diagnosis, focusing on the issue at hand and taking into account the opposing strategy. If we had started with context here we would have started with describing the growing push for copyright reform, the close networks the copyright industry has with the legislators and its clear strategy to make this about emotions, ethics and rights – not about the economy. “Piracy is theft” is an example of how this strategy looks in messaging.

Our strategy in turn is to meet emotion with economics — something that is really hard, but the only viable way when your opponent is playing the emotions card and drawing on deep networks in the legislators (as well as hosting celebrity parties with politicians).

Now, with context, objective and strategy in place we are left to devise the tactics. The tactics cover a broad set of different actions that we can take to accomplish the objective through the strategy. Each tactic listed in the plan should stand that test – to represent a way to achieve the objective through the strategy. Tactics come in many forms, and a non-exhaustive list follows.

1. Individual outreach to key decision makers. Lists of people, matching them with internal and external stakeholders.

2. Meetings and conferences. A good way to achieve scale in advocacy.

3. Third party NGO-support. Who is aligned with us and will be able to help? What do they need, and what will supporting them mean for their independence, credibility and impact?

4. Corporate allies. Are there other companies that we can work with? Industry alliances can be had both in the form of industry associations and temporary fora or bodies built for a specific plan.

5. Academic research. Is there research that supports our cause? Can it be made more visible? Shared broader? Should new research be commissioned, and if so how – so that it remains credible and useful?

6. Advertising campaigns. Is this a case where advertising may help?

7. Grass-roots campaigns. Are there grass roots organizations that care about this issue – and if so, can we legitimately support them?

8. Converts. Are there people from the other camp that we can bring over, who will testify to our benefit?

9. Language – how should the proposal be presented. Are there better ways of describing it? Frank Luntz has great advice on this in his books. The metaphors we use, the analogies employed, will matter.

10. Legal strategy. How can litigation – ongoing or planned – affect what we are trying to do here?

11. Corporate communications. What are the best communication strategies? Interviews? Opeds?

The context, objective, strategy and tactics now all form a plan – and the next thing is to implement it – we will return to that issue below, but first need to look at a couple of other models for planning.

Campaigning

Some government affairs people prefer to think about what they do as political campaigning – either because they have a deep political background, or because they think that it provides a good model for influence work — and it can, but there is reason to be careful here. A campaign has a final moment – an election – and that election is a focal point that organizes the entire campaign.

You win a campaign. A strategy or a plan creates a position of greater strength than before. Campaigning is a finite game, strategy an infinite game.

This matters – because the campaign analogy risks losing sight of the horizon and the next steps, since it is so relentlessly focused on the win/loss moment.

That said, a campaign can be a very effective way of organizing resistance to a political proposal, a bill or even an enforcement action from an agency. There are also a few kinds of legal cases and litigation where campaigning can help – but influencing courts is – as it should be – very difficult, and often risks painting you as working outside of the legitimate domains of government affairs.

When planning a campaign, your key task is to define what winning and losing looks like. Rather than a clear objective, you want to win – and you need to be really clear about what that means. This clarity will help the campaign, often fast-moving and sprawling, to make decisions on the basis of the win and work towards the same goal. A campaign without a win (and the corresponding loss) is not a campaign.

To really lean into the underlying metaphor you may want to think about winning as getting the right number of votes and construct a virtual electorate that you care about. You can model the different stakeholders as voters and look at how they vote now and what is needed for you to win. You can use the concept of “swing voters” to identify the people, companies and organizations you think you can win over, and polling can actually help to give a sense of the situation.

Tracking the vote – the percentage of the stakeholders agreeing with you – is a good way to keep score, if you manage to construct this model well.

A campaign focuses around an individual, or candidate, the person you want to have picked. In the case of a company, the candidate is the company. This means that the company should expect to be judged on backstory, character, behavior and engagement — it is not about being right, it is about being the right winner. That means that a campaign necessarily puts focus on the company. No proxies or surrogates will do at the end of the day – the candidate needs to take center stage.

A campaign builds on something that David Axelrod and Karl Rove, in their excellent masterclass on campaigning, calls ”the inferred differential” – it builds on how you are different from the other guy. This in turns means that there needs to be an antagonist to your protagonist – an opponent that you can beat.

Campaigns are about comparisons: your candidate is compared to the other guy, and it often gets personal. The opponent is unlikely to want to mend fences after the campaign, and you win at the price of acquiring an enemy. When you are fighting a government or court, this is risky – since it means that you are spending a lot of effort at building a confrontation. Any really successful campaign also thinks about what happens after the win or loss, aware that even campaigns may be multi-round.

Campaigning is done by the grid – a day by day plan where you try to build in as much work as possible. Your actions are determined by the overarching goal of winning — everything you do, every day, needs to be about winning that ultimate vote or decision at the end of the campaign. The grid is the plan – what happens everyday is the plan – you are not building a multidimensional position of strength, you are winning or losing.

The grid is filled with actions and tactics that let you sway the electorate, targeting the swing voters and focusing on changing minds, winning hearts.

We keep repeating this – winning or losing – but it really is key to understanding the campaign format.

Our own experience with campaigning is mixed. It can work – you can win – but winning comes at a significant cost. Tech industry sometimes argues that it stopped the SOPA/PIPA-proposals in the US through campaigning, but it happened – if this is to be believed – at the cost of showing their influence and size and importance to the economy. If not the moment that tech became big tech it was a moment that brought the industry closer to that position. Was this the point where the antitrust sentiment took root? That may be taking it too far, but it certainly was one of the moments that highlighted the central role that technology plays in our lives.

In the fight over the European Copyright Directive, tech companies had built both on a real grassroots campaign and on their own efforts. The campaign was painted as a heavy-handed attempt at influencing a legitimate, parliamentary process, and the tech industry lost. This loss showed something important – the more powerful you are, the harder it is to campaign – when the opponent, in this case the European copyright industry, can paint themselves as weaker and underdogs.

Money is a weak predictor of electoral success.

Campaigns are won by challengers rather than incumbents – and tech had, by the time of the European Copyright Directive, become a kind of incumbents in the eyes of the parliamentarians, and to boot they were strangers, foreigners.

If you believe you need to set up a campaign, you need to think through these costs, and the cumulative impact of campaigning — since it really will affect your ability to do regular government affairs work.

Risk analysis

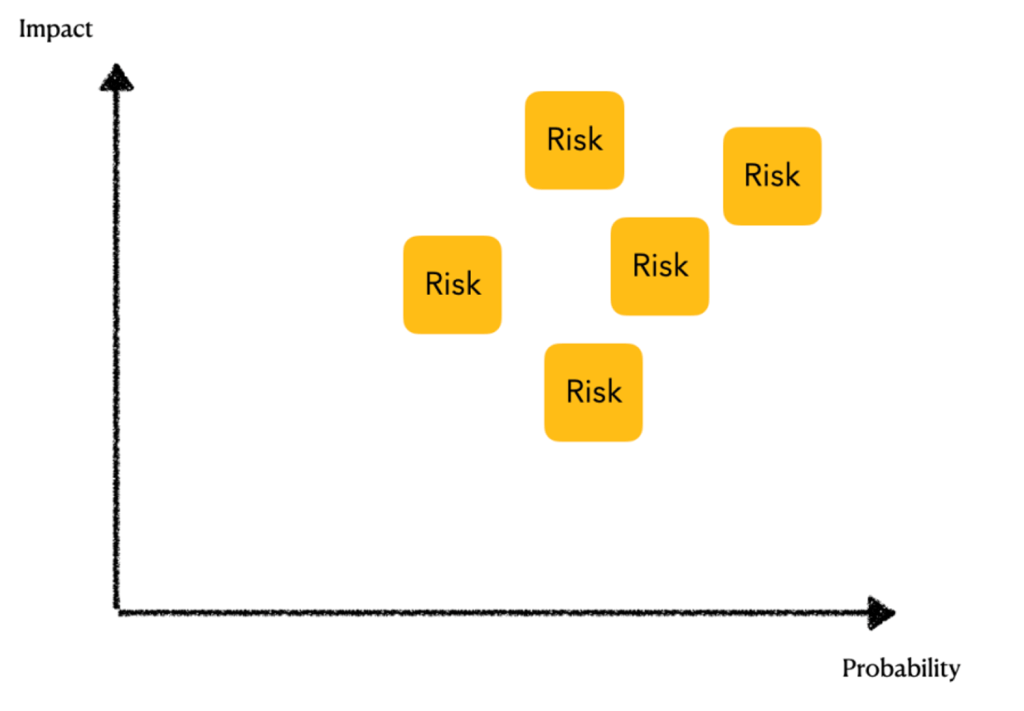

Focusing on risk allows us to ensure that we are looking at impact to the company as the core value that we calibrate against. The method is based on discovering and ranking different risks in two dimensions – impact and probability – and then examining the effort and yield in mitigating the existential and critical risks.

The first step is to generate a list of risks that the company faces. After this list has been deemed reasonably complete, those risks are ranked according to the impact to the company and the probability that they will occur.

Impact is defined broadly and covers the cost to the company (expected level of fines, lost profits, lower margins, compliance costs, litigation costs and other similar costs), loss of access to decision makers, reduced ability to attract critical talent in recruiting and higher acquisition costs for partnerships and companies we want to acquire. Impact should also take into account if a risk affects us disproportionately — i.e. is this something that specifically creates a competitive disadvantage for us? Other things that should be weighed are effects on employee morale and possible loss of market access. Impact is a broad term and should be expansively interpreted.

Probability is the probability of the risk occurring. Here the best we can do is to err on the higher side of probability, since the overall landscape is very uncertain. One important consequence of the current political climate is that our overall confidence in our probability assessment has been significantly reduced. This means that a 60% probability with only 10% confidence should still be treated as high. As low we should only treat risks that we are confident will be lower than around 10%, Medium is 20-40 and high 60 and above. This scale takes into account the current confidence challenge. Probability is best assessed by looking at factors like: is there legislation or action in the field that would lead to the realization of the risk? Are there actors actively working to bring about the risk or that would accept the risk should it occur? A lot of the risks that we face are realized by our competitors and pushed for by them, so that needs to be taken into account.

The result is a chart along these lines:

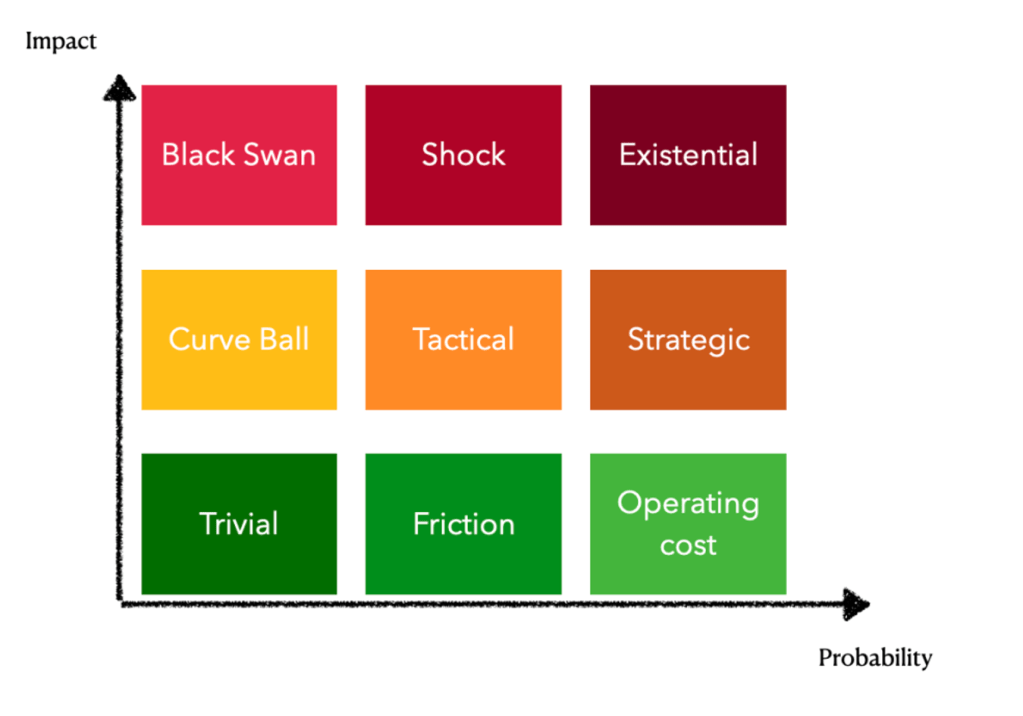

These risks can then be classified and grouped together, like this:

Once the risks have been classified this way the next step is to take those risks that have been identified as existential and critical, and classify them according to the effort needed to mitigate them and the yield that effort will give. This is to recognize that there are risks that are difficult to mitigate, and to discern which risks can be most successfully mitigated.

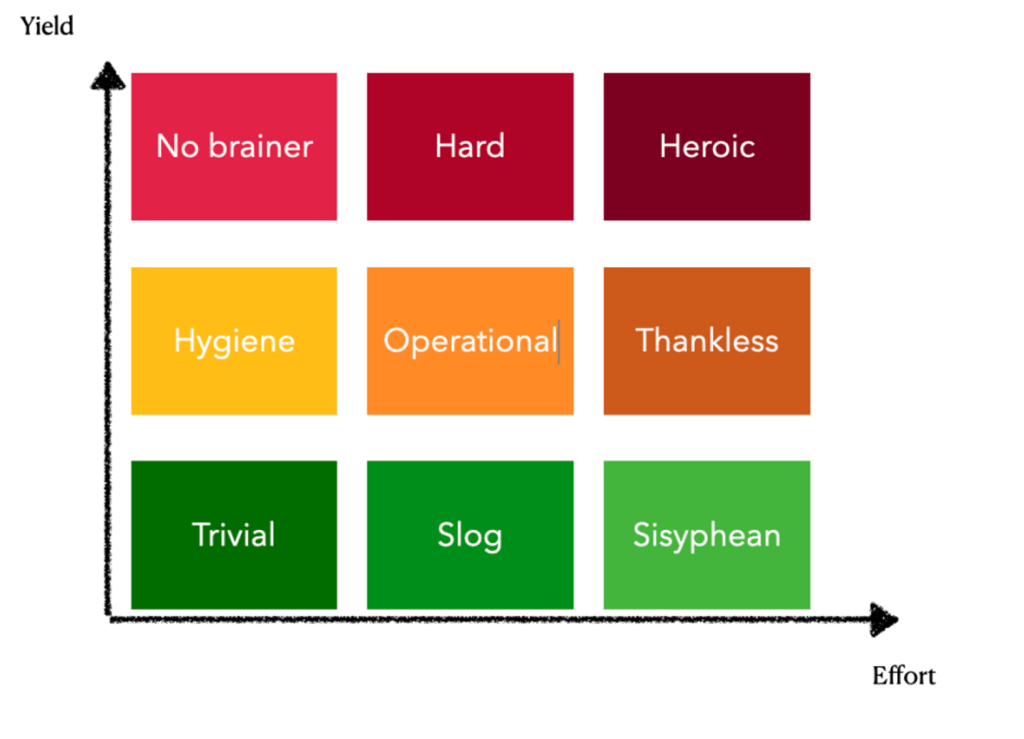

Yield is defined as the change that we believe that we can bring to an issue. Can we materially affect the outcomes, and really make progress on an issue? If so, the yield is high. If we believe that a risk can be partially mitigated we should value the aggregate mitigation in total for the risk, not for the parts that we can deal with.

Effort is the sum total of resources – money, people and relationships – needed to get that change that we would like to see. A part of the effort is also coordination complexity. Would this require significant involvement from leadership, other functions, industry, partners and customers?

The result is a chart that looks a little like this:

After having organized the chart this way, it is possible to produce a list, in the following order:

- Existential risk. Existential risk must always be addressed, even if low yield / high effort.

- Critical risk organized after no brainers, hygiene, trivial, operational, hard and with a possible addition of the heroic — but only after the first categories have been addressed.

Once this list is complete we have a tentative focus list for planning.

One additional exercise here that will allow to check for completeness and long term vision, is to examine the risks in a horizon chart. The idea here is to map the identified risks against 6, 12, 18 and 24 months and ensure that significant risks have been identified even if they are 24 months out – to the extent possible. A concentration around 6 months may signify that we are somewhat myopic and not building for the long term.

Depending on resources, you may want to focus on 6-12 months or perhaps even stretch further for some really significant high impact risks.

Models of influence

Underpinning all of the planning work is your model of how influence works. This question may seem trivial, but it is really not. The question of influence works is at the heart of any attempt to do government affairs — how do people change their minds? We have already looked at the importance of surprise and stories in the chapter about storytelling. In this section we will look at who you should be addressing.

The most common model of influence says that if you want to change anything you need to go to the top. Change happens when you speak to the minister, the president, the CEO. That is where the decisions are made, so that has to be where the influence should be applied, right? This model quickly identifies a number of so-called Key Opinion Formers – KOFs – and suggests that meeting them, persuading them and changing their minds is the most effective way to build influence.

This model, although appealing, is wrong on almost all counts, and it is wrong just because the minister, the president and the CEO is making the decisions. They will look weak if they are persuaded, and weak if they are influenced by you. They are likely to be reticent to accept invitations to meet, and will often meet with you to signal that they are listening and thinking – but cannot be seen to fold for your influence.

A more realistic model starts from using a simple model that we refer to as the logarithmic theory of influence. Under this theory decisions are made by one person, 10 people participate in the decision making process, 100s shape it and the rest are decision takers. The top, the one person making the decision, is the wrong place to go to – at least in most democracies. You want to look at the ten who participate in making the decision.

The ten – they are usually in the tens not in the hundreds – are sometimes referred to as the inner cabinet. These are the people the minister will ask for an opinion. The people who hold the pen. The ten develop the decision and shape it to the point where the decision maker feels the decision can be taken. If you know what the ten think, your ability to predict a decision is usually almost perfect. There are a few decision makers that will occasionally go against all of their inner cabinet – but they are few, and often short-lived politically.

The 100 who shape the decision are the think tanks, academics, the journalists and pundits that the ten listen to and respect. The 1000 who underpin the decision are the ones that the 100 interact with and listen to, and the 10000s that agree to the decision are the political base of the decision maker.

In any plan it is crucial identifying this network structure and laying it out. There are multiple influence points here — the political base can be interesting, especially if you can mobilize a grassroots campaign. The think tanks, academics and journalists can either reinforce each-other or create an opening for new perspectives in their disagreement. The ten are key, and need to be understood and modeled well.

One of the more modern tools available to you here is social network modeling. These models show how influence flows in a network and can be very helpful in understanding where to direct your efforts.

When you study the ten you will often find that they already have allegiances. This is no accident. A good decision maker models his stakeholders and base through the ten, through the inner cabinet, in order to be able to simulate decisions and understand how they will travel through the chain of decision making. The question is if you have the ear of anyone of them? Or if there is someone that can be injected into this circle to represent your viewpoint.

A plan lacking a model of influence has very low chances of succeeding.

Putting the plan into action

Working out the plan is about one tenth of the work. Next comes putting it into action. You have your plan, your social network map and model of influence – what should you do now? You need to create a rhythm.

All plans are executed in a cadence. If the plan is short term you may want to do a daily stand up meeting checking in on all of the aspects of the plan, problem solving and adjusting on the fly. Longer term plans can be built around a weekly cadence with check ins and flags for significant deviations.

The purpose of creating this rhythm or cadence is that this is where you will learn and adapt. No plan survives contact with the enemy, as we noted in the beginning, but as the plan is rolling out it needs to be managed through a regular set of meetings and processes.

It is easy to underestimate this part, but the reality is that this is where the plan happens. Von Moltke, our source for the quote about plans surviving contact with the enemy, knew this too and is told to have remarked ”amateurs discuss strategy, professionals discuss logistics”.

There is an immense truth to this terse comment. Logistics – how you get things done – is much more important than the plan. Talent for this needs to be built early on in a government affairs team, and cannot be overvalued. A government affairs team will attract a lot of brainy individuals, political commentators and policy wonks – and they all are essential – but without execution and logistics their analysis and strategies will fall flat.

Very few government affairs teams have operating officers, and a classical mistake in building a government affairs team is to build expertise in issues, but not build an operational project office that can run the plans.

Now, when you have decided your cadence, there are a few stock items that you should have as standing items on your agenda.

1. Major developments. What has happened that affects the plan, and where do we need to adjust? This is the most important point in any execution meeting and it is the agenda item that ensures that you learn.

2. New ideas. Given what is happening people may have new ideas – they should not be discarded. A focus on execution does not preclude looking at new ideas over time and looking at how they can be integrated. Your team should not be thinking only at the beginning of the plan.

3. Resource needs. As leader your most important question is if everyone has what they need. And there should be no shame or hesitancy around admitting that someone needs help or more resources.

4. Checking failure points. Fore each plan you should identify how it breaks. What can happen that will make the plan useless or so much more costly that there is nothing to be done? Those failure points need to be kept firmly in mind.

These points are a start – there are others, like checking in on allies and opponents – thinking through how to boost and neutralize them – but this is the core.

Thinking in capabilities

Plans, strategies and objectives dominate the discussion, but they are all dependent on your team and your organization actually having the capabilities to work through what you are trying to achieve. Setting a goal means resourcing it and ensuring that you have the capabilities to reach it.

Our focus on goals and strategies sometimes obscures this obvious fact. If you really want to be efficient at planning, you also need to plan your capabilities. We will get back to this point in our chapter on building a team – but it also deserves mention here.

Without objectives?

When we examine our own thinking about thinking, one of the things that stands out most clearly is that the dominant belief in setting goals and defining objectives – as evidenced in this section. This almost axiomatic belief in our ability to set a goal and then work hard to reach it is embedded not just in us, but in most of western civilization. The image that suggests itself is someone setting out to reach the top of a mountain, and persisting until they reach the peak. So, for the sake of completeness – let’s question this and make sure we also think through the alternatives – especially if you are in a fast moving and liquid policy situation.

Objectives organize the world in terms of mental and physical journeys, but there is something peculiar about that picture. They assume we know the terrain, that we really know that the peak is the peak and that we are able to see clearly how to get there from here (and back again).

So, when we stumbled on a recent book by Kenneth O. Stanley and Joel Lehman, two computer scientists, with the provocative title Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned: The Myth of the Objective we found it a useful addition to strategic planning – what if the image of us scaling mountain sides is holding us hostage and stops us from thinking in different ways? What if our belief in objectives is excluding tactics and strategies that are much more powerful than those of goals and objectives?

After all, we should be most wary of the beliefs that we rarely examine, and as Stanley and Lehman point out:

”It’s interesting that we rarely talk about the dominance of objectives in our culture even though they impact us from the very beginning of life. It starts when we’re barely more than a toddler. That momentous first day that we enter kindergarten is the gateway to an endless cycle of assessment that will track us deep into adulthood. And all that assessment has a purpose—to measure our progress towards specific objectives set for us by society or by ourselves, such as mastering a subject and obtaining a job.”

Stanley, Kenneth O.; Lehman, Joel. Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned (p. 1). Springer International Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Objectives are silent deities governing our lives, and we are not always that clear on who sets them for us – but we can be almost entirely sure that it is very rare that it is just ourselves; more often we are beholden to the objectives of parents, friends, expectations overall in society — and objectives distilled from thinkers and writers that have long since passed away.

The economist John Maynard Keynes made this point when he noted that

“Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some *defunct economist*. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.”

But it is not only the objectives themselves, but the very idea of objectives that we risk ending up enslaved under – and the stories about success are a large part of why: never giving up, never wavering – those are the traits that we believe bring success, and if we /do/ give up the way we frame it is that we ”abandon” an objective – we leave it and in doing so we also fail ourselves.

At this point you may be rolling your eyes and wondering when we started spouting pseudo-mystical hippy evangelism – and if you do that it is because you are asking a very good question: what is the alternative? Is it some kind of fatalism? Just accepting the stagnation we wrote about in the last letter?

If we agree that objectives and goal setting is problematic – what do we do instead?

Climbing mountains, searching the seas

Objectives organize ambition and creativity. One reason we like them is that they, as Stanley and Lehman says, ”create possibility” – they allow us to imagine something and then achieve it. This is incredibly valuable, and objectives play an important role in the way human imagination recreates the world – but there are other ways of organizing ambition and creativity.

If we return to the image we used for objectives – the mountaineer scaling the mountain – and ask what other images we could think about that are about ambition and creativity we find that ambition sometimes is directed not towards a goal as much as it is directed towards /discovery/. Stanley and Lehman again:

”It’s useful to think of achievement as a process of discovery. We can think of painting a masterpiece as essentially discovering it within the set of all possible images. It’s as if we are searching through all the possibilities for the one we want, which we call our objective. Of course, we’re not talking about search in the same casual sense in which you might search for a missing sock in the laundry machine. This type of search is more elevated, the kind an artist performs when exploring her creative whims. But the point is that the familiar concept of search can actually make sense of more lofty pursuits like art, science, or technology. All of these pursuits can be viewed as searches for something of value. It could be new art, theories, or inventions. Or, at a more personal level, it might be the search for the right career. Whatever you’re searching for, in the end it’s not so different from any other human process of discovery. Out of many possibilities, we want to find the one that’s right for us. So we can think of creativity as a kind of search. But the analogy doesn’t have to stop there. If we’re searching for our objective, then we must be searching through something. *We can call that something the search space—the set of all possible things*.”

Stanley, Kenneth O.; Lehman, Joel. Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned (pp. 5-6). Springer International Publishing. Kindle Edition.

The objective remains in play – as the thing we are looking for in this vast space, or room, of possibilities. But suddenly we see why the objective is limiting us: it attracts all our attention and does not allow us to discover other possibilities in the search space. And here is the kicker: the larger and more ambitious the objective, the more it excludes entire subsets of the search space that you will now never wander into.

Now, imagine that instead of a yearly plan with objectives and key results you set out to search for solutions to your problems. The task assigned to the teams working on a problem is to explore the search space thoroughly and look not for the solution you think is the right one, but look for as many different solutions as possible – to employ something sometimes called ”novelty search” where what you look for is something new, a new mountain or even a valley in the landscape of the possible.

So far Stanley and Lehman – their answer to what should replace objectives is, if I am allowed to simplify, novelty search across the search space, looking for what they call stepping stones that allow us to solve or reformulate the problem we are working on.

Let’s say you are a tech company and you want to improve your reputation and build credibility and legitimacy in the public sphere. Rather than set an objective to hold X events, reach Y key decision makers or publish Z opens on the subject you could formulate a search for credibility-improving tasks – and then start looking at the entire search space, exploring it and working through to find things that you can try.

In a sense this is about the size of your objectives — as you search through the space of possible solutions to your problem you find simple things to try, and these things are essentially experiments, and then your objective, if you reconstruct it, is to search through the space of possible solutions consciously focusing on new solutions and seeking novelty.

The alternative to scaling the mountain is the explorer venturing out unto an unknown sea, looking for new and exciting discoveries. The opposite to objectives is not aimlessness, but exploration and discovery. Not climbing mountains, but searching the seas.

But is it all…science? Experiments?

We recognize this idea from other fields where objectives play a smaller role or are used in different ways – most directly science. The scientific method is about formulating a hypothesis, testing it and then using the test outcomes to continue exploring. Science is a surprisingly efficient method for exploring vast areas of possibility, and even if this model of science is grossly oversimplified (there is a lot more complexity to science with emotions, ideologies and substructures than the simplified model here allows for) it does give us a starting point for thinking about objectives in a different way.

Science is also our chosen method when we try to understand very complex systems, and there is an important observation here: when we deal with complex systems objectives can be positively damaging since they assume linearity where there is no linearity and articulated causality where there is no such thing.

In fact, really complex systems present an even more wicked problem: often we find that we cannot even decide on which model best represents them. Not only, then, do we not know how these systems will evolve, we also do not agree on how they can be best modeled or simplified. We suffer, then, from two kinds of uncertainty here – unpredictability and unknowability.

Or simpler: we do not know what will happen and do not agree on what it is we are observing. This state of being is much more common than we would like to admit, and researchers have suggested that we call it ”deep uncertainty”.

Researchers Henrik Berglund, Marouane Bousfiha and Yashar Mansoori have suggested, building on Herbert Simon, that we can think about the world as ontologically uncertain or epistemically uncertain – and that our response to these uncertainties varies: when it comes to ontological uncertainty, uncertainty about how the world is, we negotiate and make the world up as we believe it should be. When we are dealing with epistemic uncertainty we adapt and overcome challenges through information gathering. Berglund et al are discussing entrepreneurship and opportunities-as-artifacts, but their framework can be generalized into a broader discussion about objectives.

After all: adapting and negotiating – that is what organization really do all the time! Adapting by information gathering and negotiating by creating new opportunities, institutions and alliances.

Navigation, leadership and the difference between accountability and authority

Now, let’s bring this back to how we plan and what we do day to day. What if an organization decided to describe the key challenges it is facing in its environment – a really robust description of what is going on here – and then set out to find adaptations and negotiations that could help deal with the challenges in the environment. Would such an organization be less successful than one with clear objectives and key results? Or would it have found a better way to address the deep uncertainty that most organizations face?

In deep uncertainty research a key insight is that if we are dealing with deep uncertainty our best bet is to interact with the system and see what it produces in terms of responses. We set up a dialogue between ourselves and the environment, probing and testing – and, yes, experimenting all the time. These experiments allow us to find out more about behavioral patterns and tendencies and so allow us to find ways of adapting and negotiating.

Again, we are back to our experiments – we set out to experiment and think through the results of the experiments as we explore the overall search space for organizational success.

Sounds exhausting, doesn’t it? Much easier to just set objectives — right?

Well, maybe. But the objectives often become stunted and artificial and do they really inspire people to do their best work? What would you prefer? To come into work in an organization that is actively exploring novelty, experimenting and looking for negotiations and adaptations – or to come in and deal with a set of objectives that have been established a few months ago and either have been designed to be so abstract as to survive the complexity your organization works in (and hence feel fuzzy and less meaningful) or start to feel more and more obsolete as the environment changes?

And this leads us to another interesting insight – and that is that without clear objectives we need much better management and different organization models.

The objective and key result model risks becoming a bad prosthesis for good management – it provides clarity at the cost of flexibility, but at least you have clarity. The role of a manager in an organization organized around novelty search, interactions, negotiations and adaptations becomes much more complex; the manager needs to coordinate, sift through searches and proposals, figure out how to decide better on experiments and interactions – he or she needs to manage risk in a much more fluid way.

The objectives and key results model distributes accountability across an organization — it is the employee’s problem if they cannot reach the objectives, the manager can stand clear from the mess that ensues, and the model of performance that it encourages is individualistic; you are responsible for reaching your OKRs and it is your fault if you do not succeed.

I think we all know that this is not always true. Performance is a network concept and we perform both better and worse depending on the contexts, capabilities and networks that we have access to in an organization.

Here is an analogy – modern organizations are a lot more like ships than they are like Tayloristic factories with individuals as atomistic components of a machine. The ship depends on centralized authority, the factory on distributed accountability. This, again, is an uncomfortable conclusion for us – because it seems to suggest that we need strong leadership in our organizations, when we have been taught to think that modern leadership delegates, includes and defers to the views of the many. Strong leaders sounds almost atavistic, even if we have accepted strong-willed entrepreneurs as a part of the Silicon Valley narrative.

But I think we get this wrong: the ship’s captain also delegates, defers and includes – but with a presence and a command of the ships overall fate that clearly requires him or her to navigate the sea, and this is the key challenge in a complex environment – this navigation of the sea. And navigation requires that the leader synthesizes the whole situation and reacts to it – and ultimately the fate of the ship, the accountability, lies with the leader.

That is why they leave a sinking ship last, and not in order of the last performance review.

In her beautiful book introducing the ancient Greeks, Edith Hall suggests that Ancient Greece was a thalassocracy – it was governed by the sea, on the sea, and the Greeks themselves thought not of themselves as distinct cities (as we are often taught), but, as Homer suggests, a set of ships. The Greeks set out to discover the sea, to explore it and master it – driven by a sense of adventure and expansionism that is not unlike that of today’s entrepreneurs.

The modern organization could find no better model than this, I think, and in a thalassocracy we search and navigate choppy waters, we interact with the sea and we seek adaptations in better ships and negotiations with other ships – we experiment and learn.

So what…abandon all objectives?

Now, we will not abandon the objectives-model – and we probably shouldn’t. The value in challenging a mental model lies not in replacing it as much as it does in challenging its hegemony and allowing for us to introduce other models as well. I still like objective thinking, and I think that the core take aways from this examination for me are the following.

- In addition to objectives, we need to ensure that we also set out to search for novelty, design experiments and find adaptations and negotiations. When we plan we need to complement objectives we key searches that we want to make to explore the set of possible futures. This is essentially unpacking what we sometimes call ”incoming” and thinking about how we deal with the whims of the sea.

- Our ambitious objectives should be decomposable into existing capabilities. This is an important point about moonshots – Stanley and Lehman point out that the moon landing was ambitious, but based on technologies that were well within reach. The temptation in setting ambitious objectives is to instead set objectives that have no grounding in actual near term capabilities – and then we limit the search space in ways that are sure to be harmful.

- Learn and practice goal revision. The objectives that we do set often need to change, but most organizations lack good ways of revising their goals and so pursue these goals even when they no longer should be the key priorities.

- Learn experimentation. An organization that does not experiment is not learning, and sometimes experimentation can as simple as looking at a meeting as a way to test a message or an idea, and then diligently evaluating it. It is not that we do not try things in organizations, it is that we often do not spend the time to learn and document what we learned. This feels ”bureaucratic” and ”administrative” – when in fact it is the core of what a learning organization should be engaged in. If you do not believe me, believe Jeff Bezos: ”Our success at Amazon is a function of how many experiments we do per year, per month, per week, per day”. Now, the pithy CEO quote is not a favorite genre of mine, but here I think he is absolutely right. A good place to start is Stefan H Tomke’s Experimentation Works: The Surprising Power of Business Experiments.

- Chart and re-focus on capabilities. This is an old pet peeve of mine, and I aim to return to it, but organizations would benefit from distilling from their diagnosis of the environment a set of capabilities that they need to have – things they need to be able to do routinely and well – and then set out to build and maintain those capabilities. It is clear for anyone who studies the most action-focused organizations of all – the military – that their relentless focus on their capabilities and those of the enemy is key to their success.

If we do this AND think through achievable objectives that build on near-term capabilities we will be more successful than if we end up a single-mental-model pony with objectives as our only tool. And it also makes work a lot more interesting!

Conclusion

This chapter has tried to give an overview of the importance of planning, the methods you can try and the alternative approaches out there. We hope that it has given you a sense of how planning can help you build a government affairs team that really is able to make a difference for your organization – as well as help you think through the challenges that planning entails. Here are some questions to think about:

- What does a successful story of your team look like from 18 months from now? Write it out, explore it!

- What is going on here? Spend time on understanding the stories that are out there, and explore how they relate to your success story (and by all means, also write a failure story!).

- Are you focusing on the right risks? The no brainers? Or are you hunting the heroic ones?

- Do you have the capabilities you need? Can you list them? Work on them on some way?

- What would it look like if you ditched planning and applied novelty search instead, looking for the next move rather than planning ahead? Are there cases, situations in which this would help you?