Why do some tools never quite work?

If you ever worked with any larger project, in a PR or policy or even in politics, you will be familiar with the idea of stakeholder mapping. It is, however, an idea that often is only half-baked and gets stuck in different failure modes, the most common of which is the production of a sad spreadsheet that sits withering away in a cloud drive somewhere after the initial enthusiasm and workshopping is gone. But if you can get it right, stakeholder mapping is really important and fun – but you have to shift your views slightly before you can make it useful.

First, you have to really lose the idea that there is someone who has a stake in what you do. It is a static and slightly silly idea, and seems to suggest you should focus on who should be included, rather than the problem you are trying to solve. Here we can apply a trick and ask what a stakeholder map really does when it functions well – and one preliminary answer is that it allows you to effectively allocate attention and resources across a number of actors who can influence outcomes you care about for a specific area. If you want a project to be successful, it is the people who will be impacted by it, but also the people who can tell the story about the projects success. If you want to shape a legislative debate it is the people engaged in that debate, but also the people affected by it through second or third order effects, but who do not yet know about it. What you want is to understand the who of your particular concern, the dramatis personae. So it is not about stakeholders as much as about all of the people who can act and so influence the project you are working with.

(This raises a question that we will have to dig into more, but should flag here, and that is how general a stakeholder map can be. The answer is that there are useful general tools in this field, but their use is limited to broader strategic analysis (we will come back to this).)

Second, you have to lose the idea that you are producing a map. You will be able to do that as well — but what you really want is not so much a stakeholder map as a stakeholder model. The model needs to represent your best-effort theory of how the project you are working on is going to work out. This means that you start from the end, from the outcome you want and then you need to think about how that outcome becomes more or less likely.

In one sense, then, an actor model (that is what we will call this rather than a stakeholder map) can be thought of as a model that predicts the probability of your outcome, given the probability that actors will support or work against the outcome in different ways and with different levels of efficiency. The simplest model of this is something like a model of a parliament, where you are trying to predict the outcome of a vote. That model is also useful, because it allows us to have an interesting discussion about the level of resolution that we should aim for. If people in parliament vote along party lines, the number of actors you need to model is not equal to the number of parliamentarians, but the number of parties that you need to get on your side. This leads us to our third point.

Stakeholder mapping often fails because it stops at recognising that a certain group has a stake in the outcome. It does not describe why they have a stake or what it is that they care about. Actor modelling needs to take into account what each group is trying to maximise – that is, how they can be influenced – and what level of impact they can have on the final outcome. This is hard, since most actors are not linearly trying to maximise something: they may only be interested in swinging their vote if they are guaranteed a certain discrete outcome – e.g. getting a provision in a bill – and not just getting 10% more funds to a specific interest group, say.

But without this feature in your model – a sense of what it is that the actor in question desires – the model will be less useful. You also need to know how much of an influence the group can bring to bear: a party with 5% in the parliament maxes out at 5% if they have no extra levers to bring other parties with them.

What slowly emerges here is that what we want is not a stakeholder map as much as a negotiation model. And when we phrase it that way it also becomes reasonably clear that we need to look for exactly what the object of negotiation is.

This shift from stakeholder mapping to negotiation modelling may seem like a big step, but it really is not. The classical stakeholder map is just a first step in building a richer negotiation model, and it is easier to start thinking about the negotiation model at the outset.

Let’s then turn to what we mean with the object of negotiation.

We are always involved in negotiations of different kinds. The word itself could be read as a lack of leisure (neg-otium) and so we immediately see that all work is a form of negotiation, every serious engagement and project is really a negotiation. We often think that negotiations are about things like salary or the price of something we want to buy, but that is a narrow perspective to take. In fact, most modern work is a set of nested negotiations where we ware negotiating things like time, money, identities and different courses of action.

Public policy work is, in a useful abstraction, a negotiation around the regulatory and political environment an organisation operates in – consisting of many nested negotiations around laws, enforcement actions, investments, employment, social and economic impact, taxes…and these nested negotiations require an understanding of who is involved at different levels.

Coming back, then, to our question of the coarse-graining of these models – or the generality of them – we can say the following: it is useful to think about the macro-negotiation the encompasses all the nested negotiations an organisation is involved in, but in developing that model you should only look for the level of specificity that is helpful for discussions about the macro-level. You then need additional models of the rest of the different negotiations, building these out to the precision where you can understand how to work with them.

Modelling an organisation’s macro-negotiation with society can certainly lead to some really interesting insights.

The first insight is about who actually participates in the negotiation. A simple example is how labor unions have become increasingly more important in how tech companies negotiate their political environment. And this also shows us an important part of negotiation modelling: you need to dynamically update the weighting of not only the actors in the negotiation, but also adjacent possible actors that could step into it, or that you want to include in the negotiation to change the nature of it. A negotiation evolves very differently depending on who you include in it – and this is another reason stakeholder mapping often fails: it maps the only the existing parties. This is also a question about representation and inclusion! Who is at the table matters.

The second insight is how the object up for negotiation shifts and changes. One of the perhaps most common problems is that different parties in the negotiation negotiate about different things. An early, and somewhat simple, examples was the way in which many tech companies thought that policy discussions were about what was best for the web, assuming its globalised nature and technical openness were agreed parameters of the discussion – whereas the political negotiation was really about the same things that it has always been about – how we live together (and this includes issues like control, sovereignty and accountability). When governments started to talk about data localisation, many tech advocates reacted with incomprehension, noting that this would lead to messy network topologies and inefficiencies – something many traditional actors were fine with as long as they could control the new virtual territory they were faced with. What is on the table matters.

The third insight is about the duration of the negotiation. Many negotiations resemble infinite games, where the negotiation in itself has a value for the participants. Democracy is like that: we will never reach a point where we say ”ok, that is it – we are done: democracy completed” — the very point of democracy is that it is an infinite negotiation of values, positions and futures under some very specific conditions. We see this in how democracy fails as well: when people no longer feel that they are taking part in a negotiation, but that they have become the object of the negotiation, well, then democracies turn into a game played by a small elite. Even for companies, some negotiations are very long – this goes especially for new entrants into old industries, and underestimating the time it will take to negotiate a new equilibrium is almost always a mistake. If you are a startup entering a regulated market, you will find yourself upsetting an old negotiation and often the more new parties you can introduce to that negotiation, the better! In energy, health, finance and many other similar industries technological change has opened new negotiations that are becoming increasingly more heated. How long you sit at the table matters.

The fourth insight is that all negotiations need a host, they occur somewhere and the locus of the negotiation is often key to how it ends. In military strategy this is often referred to as terrain – and different kinds of terrain require different strategies and tactics. Stakeholder mapping often abstracts away the terrain – the environment in which the negotiation plays out – and this leaves you with a weaker model. Whose table it is matters.

The fifth insight is how important it is to diagnose the situation accurately. An accurate description of what is going on here – the Rumelt question – can be the key to success in a negotiation. The reason is simple: you need to model a negotiation starting from the preferences and desires of the different parties that engage in it. We touched on this in the beginning – modelling desire is a key to understanding a negotiation, and note that this is not just about what someone wants in the negotiation at hand – it is equally about what they desire overall: your negotiation may only be a small part in a larger one, and if you find another way to fulfill their motivating desire the whole problem can go away. Why people are at the table matters.

If we understood this, without any spreadsheets, we would be in quite a good position to act.

Tools

Overall, when thinking through how you model the actors in a negotiation, there are a couple of different simple tools that can be helpful. One tool, or method, is simply to map them across influence and alignment:

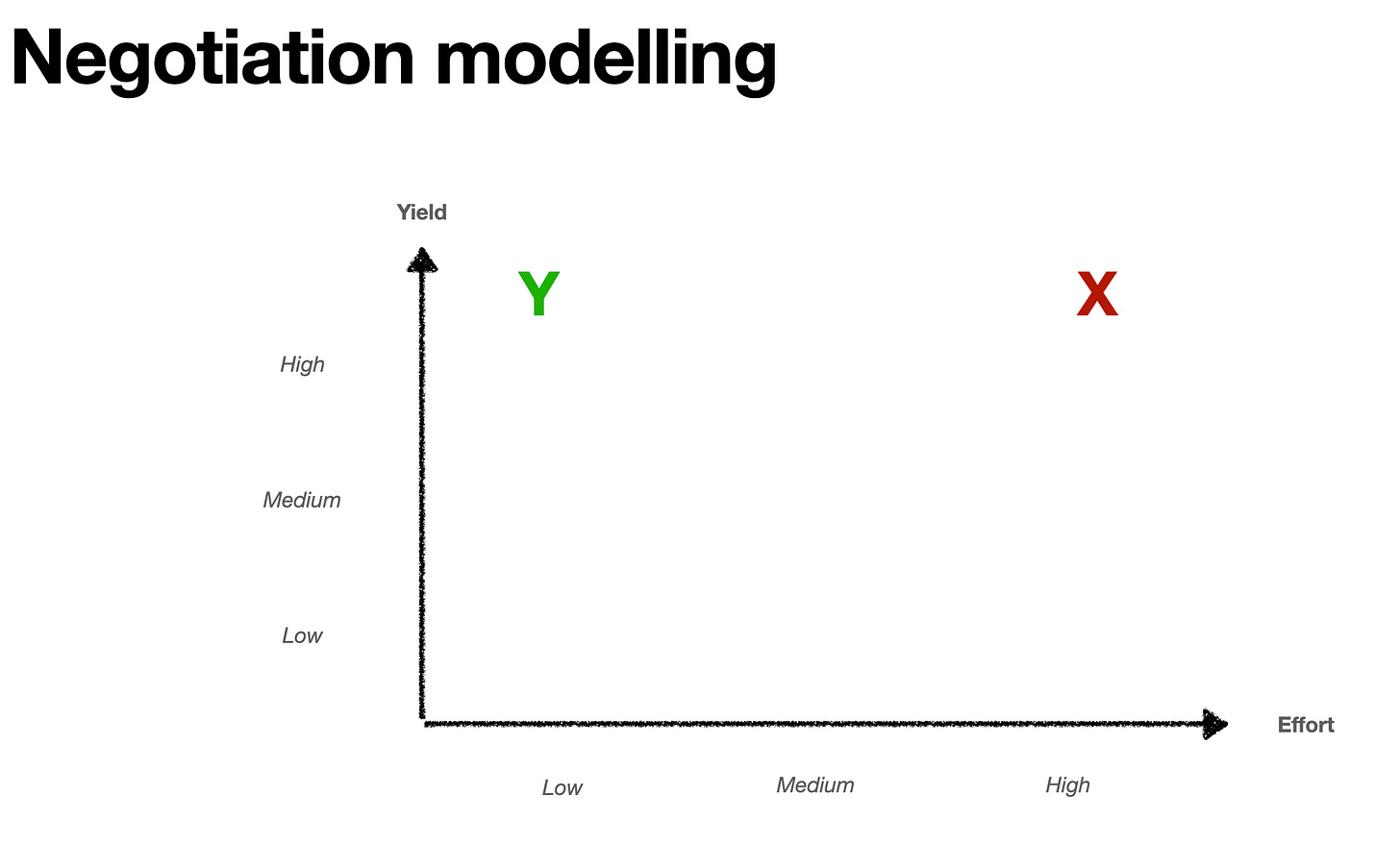

This simple map gives you an idea of where the different actors land and where there are empty categories in your on-going negotiation. Another mapping that can be helpful is to look at yield and effort – how much would it take to get someone to change their opinion? Many operations make the mistake of going after high yield / high effort (X in the chart) actors rather than exploring if there are actors that could have high yield with lower effort (Y in the chart). The allure is clear to see – changing X’s mind is a heroic task, after all — but is it the best way for you to spend your resources and time?

I mention this only because I have seen organisations often decide that they should find their worst opponents and spend time on converting them, rather than looking at the possible key converts or converts and what the value of shifting their position could be, and at what cost that can be done. There is something in us that makes us want to convince the people who hate us to love us instead, but it is questionable if that heroic task is worth it in most cases.

It probably isn’t.

Another to map the participants is to look at what their main motivation is. There are several different ways of doing this, but one simple schema is the pay-out/persistence schema where you categorise participants in a negotiation as primarily motivated by money or morals (that is, by economic gain or values) and then try to determine if they are in the negotiation because they think it is an opportunity or because they are committed to it in an a more existential way (is it a nice to have or a must have). This allows you to identify the actors that could be bought off (the money / opportunistic ones) and the ones that are likely to persist no matter what (the values / committed ones). The opportunistic value-seekers are often gadfly intellectuals or others that tend to be less effective, and the committed money seekers are the actors that think you are eating their lunch.

A negotiation with its centre of gravity on the commitment side is far more difficult that one that is more opportunistic, and often likely to last much longer.

Another thing to look for is how much someone can move. You should try to figure out – for all the actors or stakeholders – what their option space looks like. When looking at a negotiation, it is less helpful to assume that all possible solutions are available – almost every actor will be limited by a number of different factors, or nested negotiations that they are a part of. So determining their individual option space is really key.

This space can then be widened or reduced, but if you do not know what it looks like you are unlikely to be able to find a good outcome .

So what?

There are a handful of ideas that everyone agree should be useful, but still end up being really hard to execute on. Tools that should be powerful, but end up never being used – and stakeholder mapping is an example of that. There is a reason for this, and that is that we engage in stakeholder mapping in a spiky way: we do it once every year, perhaps, and then end up with a document that sits in a drive somewhere. And on top of that we often assume we know what it means: it sounds clear enough, right? We should map our stakeholders – but here, as in all cases, we should ask why, for what purpose are we doing this.

What is the function of a stakeholder map?

One possible function, I have argued, is to understand the negotiations you are involved in better, and using this model for stakeholder mapping is often both fun and enlightening. So what can you do?

- First, figure out what the negotiation is about, and be intentional about describing that. Focusing on a specific negotiation will allow you to more clearly determine who is (or could be) engaged in it.

- Second, spend time not just on who the participants are, but also what they want and how much they want it. Surface mapping is less helpful than a motivational map that clearly sets out both preferences and commitment.

- Third, use the negotiation model. Put it up on a wall, make it into a standing agenda item – examine how you are doing with the different actors, and if they have become more or less likely to align with you. If the tool you are building is not used, it serves little purpose to develop it.

- Fourth, test the model with trusted partners. An organisation will often have blindspots and miss obvious details about the participants in a negotiation.

- Finally, don’t shy away from playing with formal models as well — game theoretic analysis of negotiations are both interesting and often quite revealing. Sometimes when modelling the negotiation you will find that it does not matter what you do to convince the participants, because the dynamic of the game is such that almost all moves are forced.